Making Connections To Native Fruits

Did you know that some of the fruits grown in the HOEC Community Orchard are in fact native to our region of the Pacific Northwest, or to North America at large? From the Blackcap Raspberry to the American Persimmon, some of our favorite fruits now in cultivation got their evolutionary start on lands we continue to share with their wild relatives.

Read on for a brief roundup of some of our favorite indigenous fruiting plants from the Orchard’s collection, and come visit us to learn more about them!

Evergreen Huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum)

This wild relative of the blueberry (also in the Vaccinium genus), makes for a very attractive hedge plant in addition to producing some of the tastiest wild berries in our region, making it a favorite of gardeners and growers alike. It favorites acidic soils, but can grow in sun or shade. Its range is somewhat limited: west of the Cascades in the Pacific Northwest, from British Columbia to California. Along the California coast it commonly occurs in redwood forests, but dwindles and becomes more sporadic further south.

Blackcap (Rubus leucodermis or Rubus occidentalis)

Also known as “Blackcap Raspberry,” Whitebark Raspberry,” or simply “Black Raspberry,” this fruit is a caneberry closely related to both blackberries and raspberries, and is a volunteer favorite here at HOEC! There are numerous named cultivars currently found in cultivation, but most are bred from either of two species indigenous to North America: Rubus leucodermis (which occurs predominantly west of the Rockies, from British Columbia to Southern California) or Rubus occidentalis (found predominantly east of the Rockies). Both wild species are exceedingly alike. The Latin name of the Western occurring species, “leucodermis,” means “white skin,” referring to the often powdery white appearance of the canes. Both species occur in open, shaded, or partially shaded forests and woodlands.

Thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus)

An extremely common site along shady or forested roadsides and Riparian habitats in the Pacific Northwest, thimbleberries are a distinctive cousin to red raspberries and share many of their characteristics. They are sweet-tart, bright red when ripe, and possess hollow cores (formed by the fruit freely separating from the carpel) that lend themselves well to “capping” little fingers like a thimble (hence the name)! Thimbleberries have a fairly wide range; they occur from Southeastern Alaska to the Mexico border, and from the temperate forests of West Coast as far east as the Great Lakes region.

The fragile, soft, somewhat seedy nature of thimbleberry fruits has not made them viable candidates for commercial cultivation or distribution, but they are commonly grown in native plant gardens to provide food for wildlife. Native Peoples throughout the Northwest relied on the new shoots as well as the ripe berries as part of their traditional food ways.

Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia)

A North American native beloved in just about every region where it occurs, this fruit is known by many names: “serviceberry,” “saskatoon,” “juneberry,” “shadbush,” and “sarvisberry” are just a few! The fruits are a berry-like pome, reddish to dark purple with a waxy bloom, and sweet when ripe. The plant occurs in a variety of habitats, from forest understories and the edges of woodlands to open, rocky slopes and prairies.

Amelanchier alnifolia is only one of a wide variety of Amelanchier species found throughout North America, although they are notoriously difficult to distinguish from one another!

Osoberry (Oemleria cerasiformis)

Previously called “Indian-plum,” this fruit is now known by the name “osoberry” or “oso plum.” The greenish-white to white flowers of this plant emerge in dangling chains very early, in late winter or early spring, and are often some of the first flowers to bloom here in the Pacific Northwest. They are a common sight in dry to moist, open woodlands at lower elevations west of the Cascades, from British Columbia to California. Osoberry is the only species in the Oemleria genus, and is a close cousin to the stone fruits of the Prunus genus— reflected in its clusters of dangling fruits, which contain large pits similar to plums.

Osoberry is dioecious, meaning it requires a male plant and female plant in order to fruit. The fruits change in color from yellow to a dark purple or bluish-black as they ripen, and are more tart in taste (often bitter or astringent when unripe) than true plums, with sweetness varying greatly from plant to plant; Nevertheless, osoberry has been eaten fresh and dried by Native and First Nation Peoples throughout its range, particularly in the Pacific Northwest.

The following plants, which you can also visit at the HOEC Community Orchard, are not actually native to Oregon or the Pacific Northwest, but do trace their wild origins to other parts of the United States and Canada. No matter, we still find them tasty as well as beautiful, and are very glad they can be successfully cultivated in our bioregion!

Aronia (Aronia melanocarpa)

Also known as “Aronia berry” or “black chokeberry,” this deciduous shrub is native to the Eastern states of North America and can be found in moist forests and swamps. When cultivated here in the Pacific Northwest, Aronia is hardy, prolific, and not prone to pest or disease. The berries are dark, small, and shiny black, and form in clusters. Although somewhat mouth-puckering if eaten raw, Aronia berries can be quite tasty and nutritious when processed into juices, sauces, jams, etc.!

Check out our blog post, “Learn to make Aronia Wojapi,” to learn about a traditional Native American preparation of Aronia berries.

American Elderberry (Sambucus nigra ssp. canadensis)

It’s true that we have two species of Elderberry indigenous to the Pacific Northwest (Blue and Red Elderberry), and we do have one Blue Elderberry that you can visit at the Orchard, but the elderberries that we grow here at HOEC for their fruit, Sambucus nigra ssp. canadensis, are actually native to the temperate regions of North America east of the Rockies and north into Canada.

Much like Aronia berries, elderberries need some processing in order to truly shine— their fruits and flowers are more often processed into jams, jellies, syrups, wines, and cordials rather than eaten fresh. These recipes have been popularized by culinary traditions originating throughout Europe and the British Isles in particular, but although European Black Elderberry (Sambucus nigra) is also still widely cultivated, most of the cultivars you’ll encounter for sale in our area (including the two we grow here at HOEC, “Nova” and “York”) have been developed from wild genetic stock of the American Elderberry in order to better adapt to the growing conditions of our North American bioregions.

You can learn more about Elderberries (of many different kinds!) and get some recipe inspiration in our blog post “All About Elderberry”!

Common PawPaw (Asimina triloba)

Pawpaws are the largest fruit indigenous to North America (excluding gourds, of course, which are technically classified as fruit!). They favor rich, shady bottomlands and often forms dense thickets where they occur in the wild. Native to the Southern, Eastern, and Midwestern States, pawpaws are experiencing a recent rise in interest as a cultivated fruit in the Pacific Northwest. The fruit ripens from greenish to a bruised-looking yellow, and has a sweet-tasting, custardy texture reminiscent of bananas, pineapples, and mango. Supposedly, chilled pawpaw was George Washington’s favorite dessert, and it’s quickly becoming a fan favorite here at HOEC too!

Check out our blog post, “Pawpaw Perfection”for more of a deep dive into cultivating, propagating, and otherwise enjoying this unusual and unique fruit!

American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

Most folks who visit the HOEC Community Orchard are familiar with the astringent and non-astringent persimmons of Asian origin (Diospyros kaki) more commonly sold in grocery stores in the winter time, but many are surprised to learn that there is a species of astringent persimmon native to North America, which we grow here at HOEC: the American Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)! In fact, the English name “persimmon” is derived from the Powhatan (Algonquian) words “putchamin,” or “pessamin,” meaning “a dry fruit.” American Persimmons are not native to our area, but originate instead throughout the South Atlantic and the Gulf States.

We have lots more information about these fruits in another blog post: Pick a Peck of Pretty Persimmons, which we highly recommend checking out for further learning (as well as for some truly tasty recipes)!

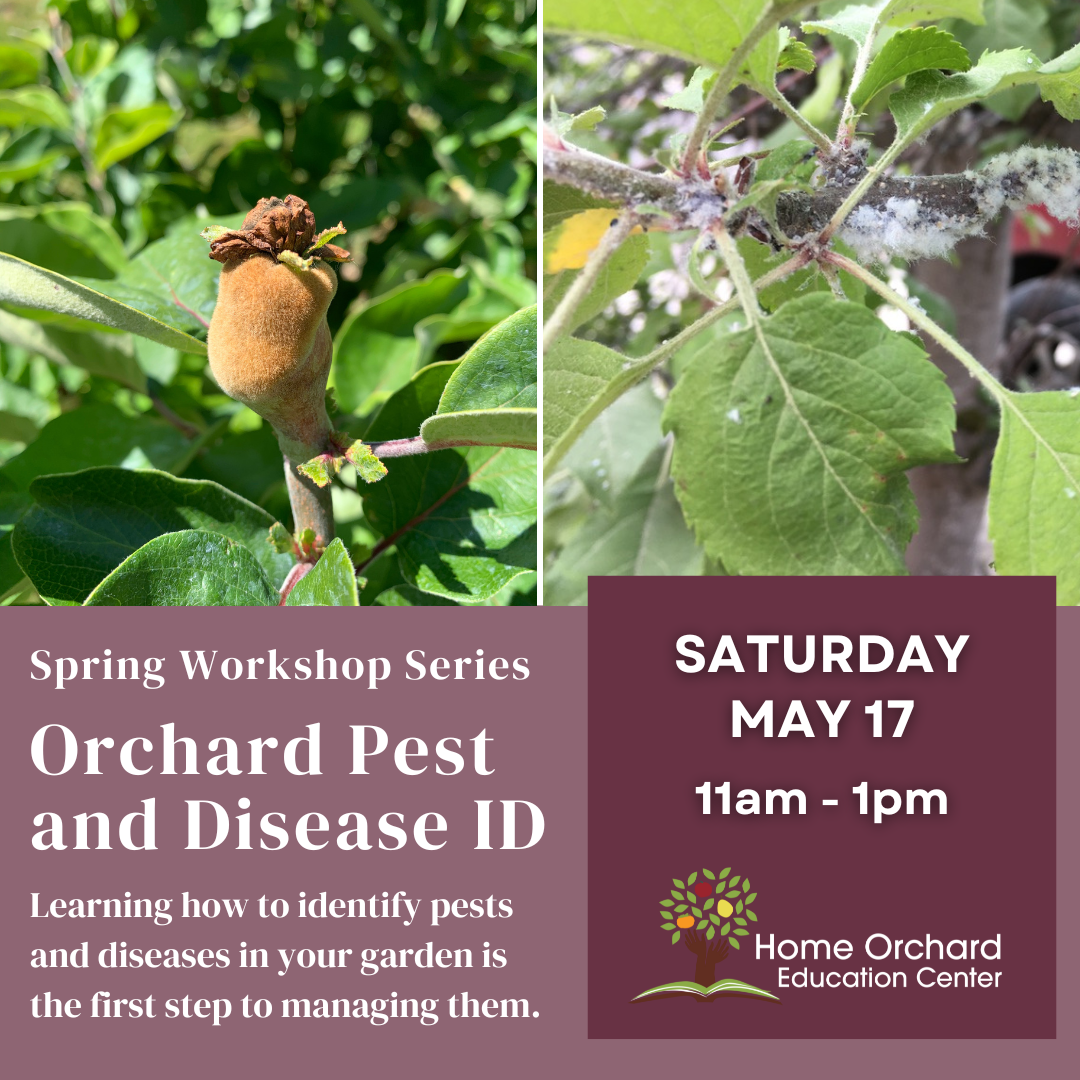

Don’t take our word for it— come visit the HOEC Community Orchard to learn about these and other fantastic fruits up close and in person! Better yet, sign up for one of our many upcoming Hands-on Workshops to get up close and personal with them.